Ghost town on reclaimed land in the Straits of Johor, Singapore, Malaysia

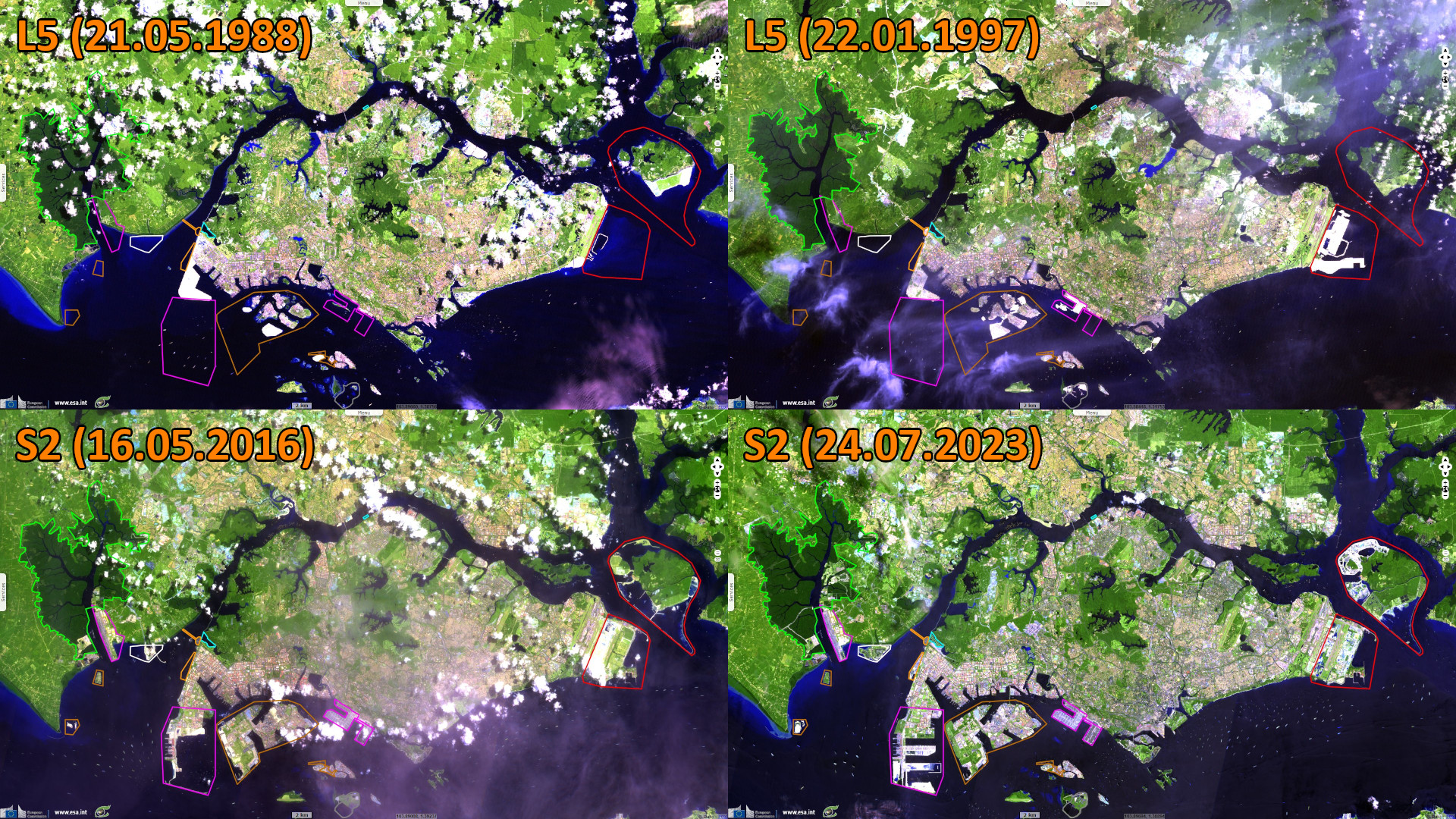

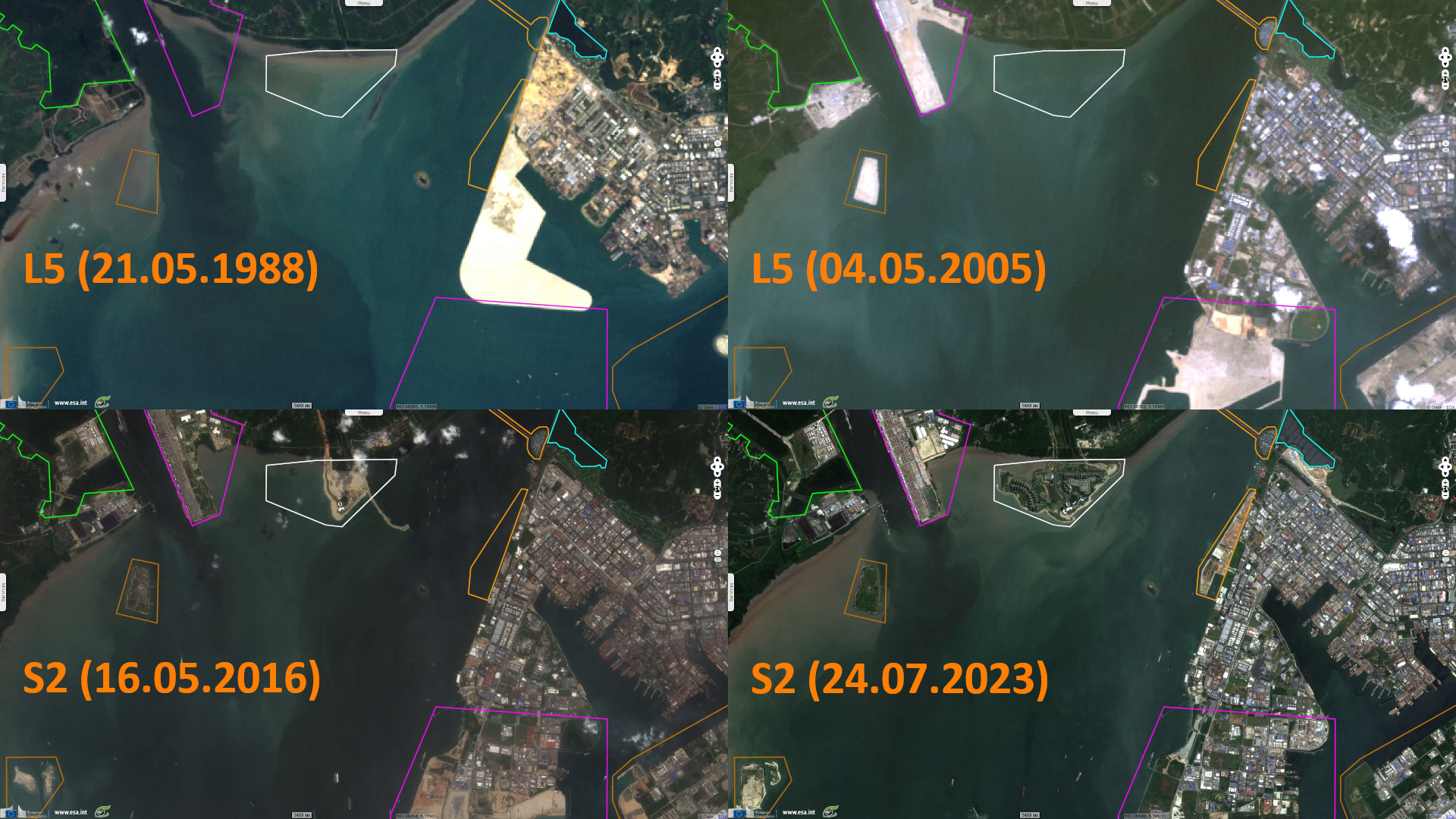

Landsat TM acquired on 21 May 1988 at 02:46:50 UTC

Landsat TM acquired on 22 January 1997 at 02:40:24 UTC

Landsat TM acquired on 04 May 2005 at 03:03:37 UTC

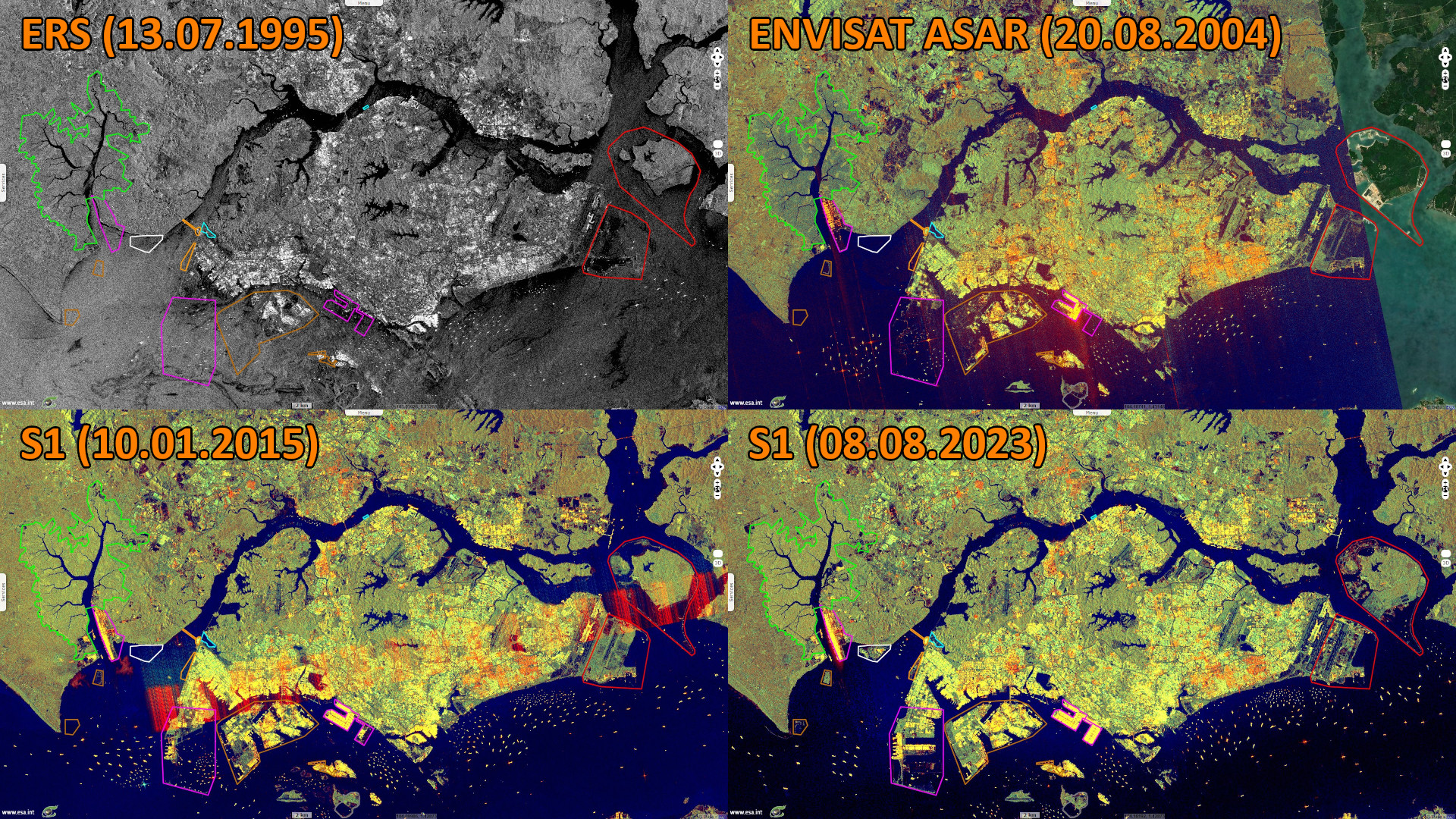

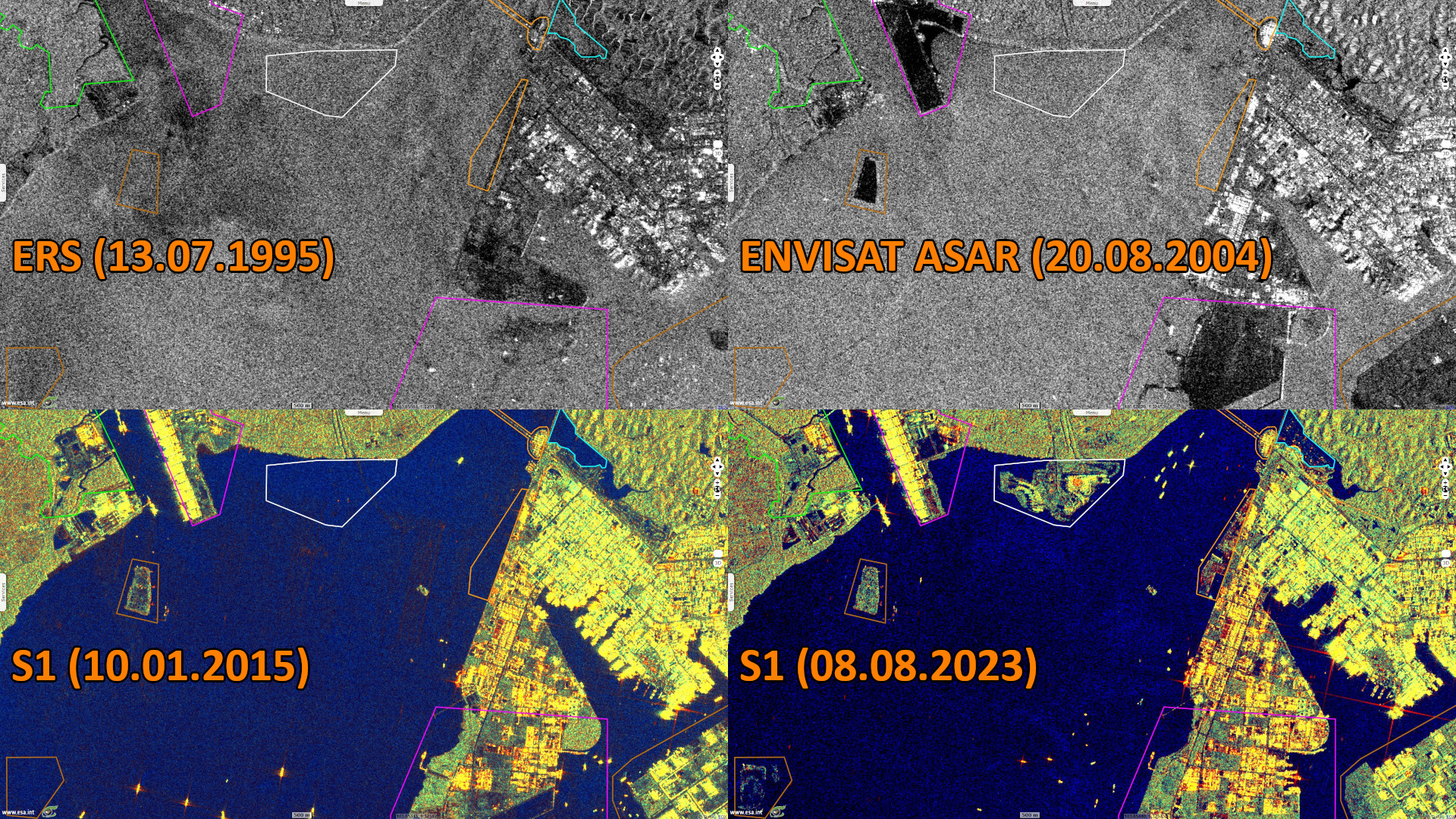

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 10 November 2014 at 11:24:50 UTC

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 16 May 2016 at 03:37:42 UTC

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 24 July 2023 at 03:15:29 UTC

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 19 August 2023 at 11:25:45 UTC

Landsat TM acquired on 22 January 1997 at 02:40:24 UTC

Landsat TM acquired on 04 May 2005 at 03:03:37 UTC

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 10 November 2014 at 11:24:50 UTC

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 16 May 2016 at 03:37:42 UTC

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 24 July 2023 at 03:15:29 UTC

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 19 August 2023 at 11:25:45 UTC

Keyword(s): Coastal, archipelago, islands, urban planning, infrastructure, erosion, Ramsar wetland, Singapore, Malaysia

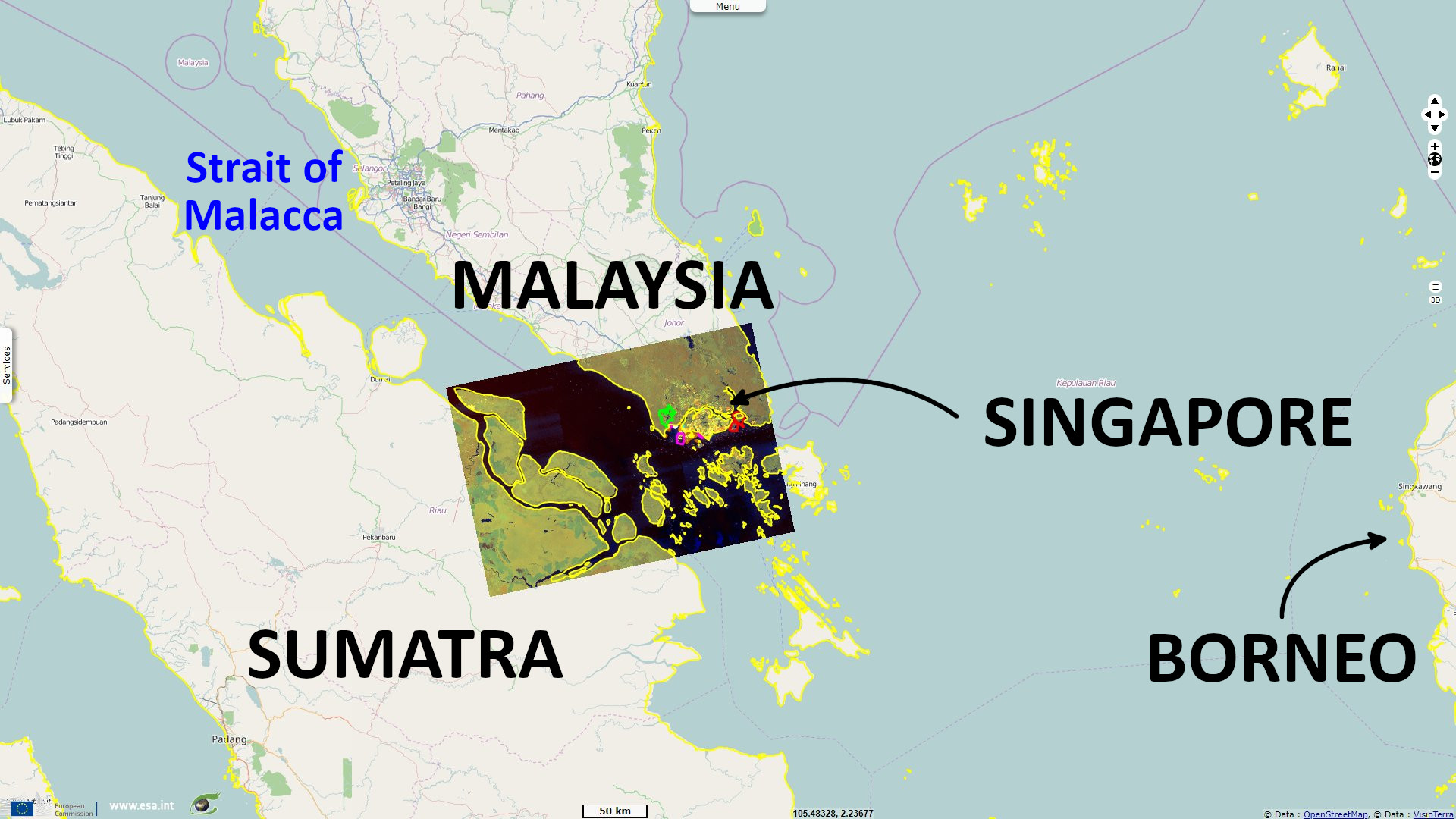

A city-state built on an island at the tip of the Malaysian peninsula, Singapore has transformed itself from a landscape of mangroves and coral reefs into a postcard of skyscrapers and reclaimed land to meet the needs of an ever-growing population. An article publised on Bloomberg explains: "During a half-century of independence, Singapore has fought to expand its territory, inch by hard-won inch. On the tip of the Malaysian peninsula, the island city state piled up sand to expand its coastline and reclaim land from the sea. In that time, Singapore has grown by one-quarter, adding land mass more than twice the size of Manhattan. At 736 sq km, Singapore is now approaching the size of all five boroughs of New York City. It plans to grow an additional 4 per cent by 2030. It’s a striking accomplishment, given that many other coasts are receding because of rising sea levels, a result of climate change."

"Roughly one-third of Singapore is less than five metres above sea level, low enough for flooding to cause punishing financial losses. Some of its most prized property sits on vulnerable land: the skyscrapers overlooking the Marina Bay waterfront, known for its luxury mall and casino, and the towers that house giant banks such as Singapore-based DBS Group Holdings Ltd., Southeast Asia’s largest, and UK-based Standard Chartered Plc. Assuming 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, prime real estate in the city worth US$50 billion faces a high risk of flooding, according to Bloomberg estimates using data from real estate company CBRE Group Inc. Another endangered, and vital, part of the country is Jurong Island, where Shell Plc and ExxonMobil Corp. have oil and petrochemical operations."

"In 2019, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that Singapore would need to spend S$100 billion over the next 100 years to protect against rising sea levels. The government has since put S$5 billion towards a coastal- and flood-protection fund. Government authorities are already considering storm surge barriers on Singapore’s waterways. The barriers would generally be open, so ships can travel to their destinations. But during a big storm, they would close, encircling the city’s industrial areas. Other possible measures: raising the height of current coastal reservoir dykes; tide gates, which block water; and more embankments, typically raised piles of earth."

This article adds: "To protect shorelines properly, mangrove forests should sprawl for hundreds of yards. In neighbouring Indonesia, they can even stretch for miles. In Singapore, mangroves can reduce storm wave heights by more than 75 per cent. Mangrove forests also soak up to four times as much carbon as rainforests. But mangroves alone aren’t enough. Singapore is studying whether it can combine the trees with other barriers, called revetments, often made of stone or concrete."

"Singapore is taking a page from the Netherlands, one-third of which is below sea level. The Dutch built sea walls beyond their coastline, creating new tracts of land they call polders. A bean-shaped plot of land on Pulau Tekong is the first polder in Singapore. Polders use less sand than the kind of reclamation Singapore has used in the past. That’s a huge advantage because it’s one of the world’s biggest importers of sand, which is expensive."

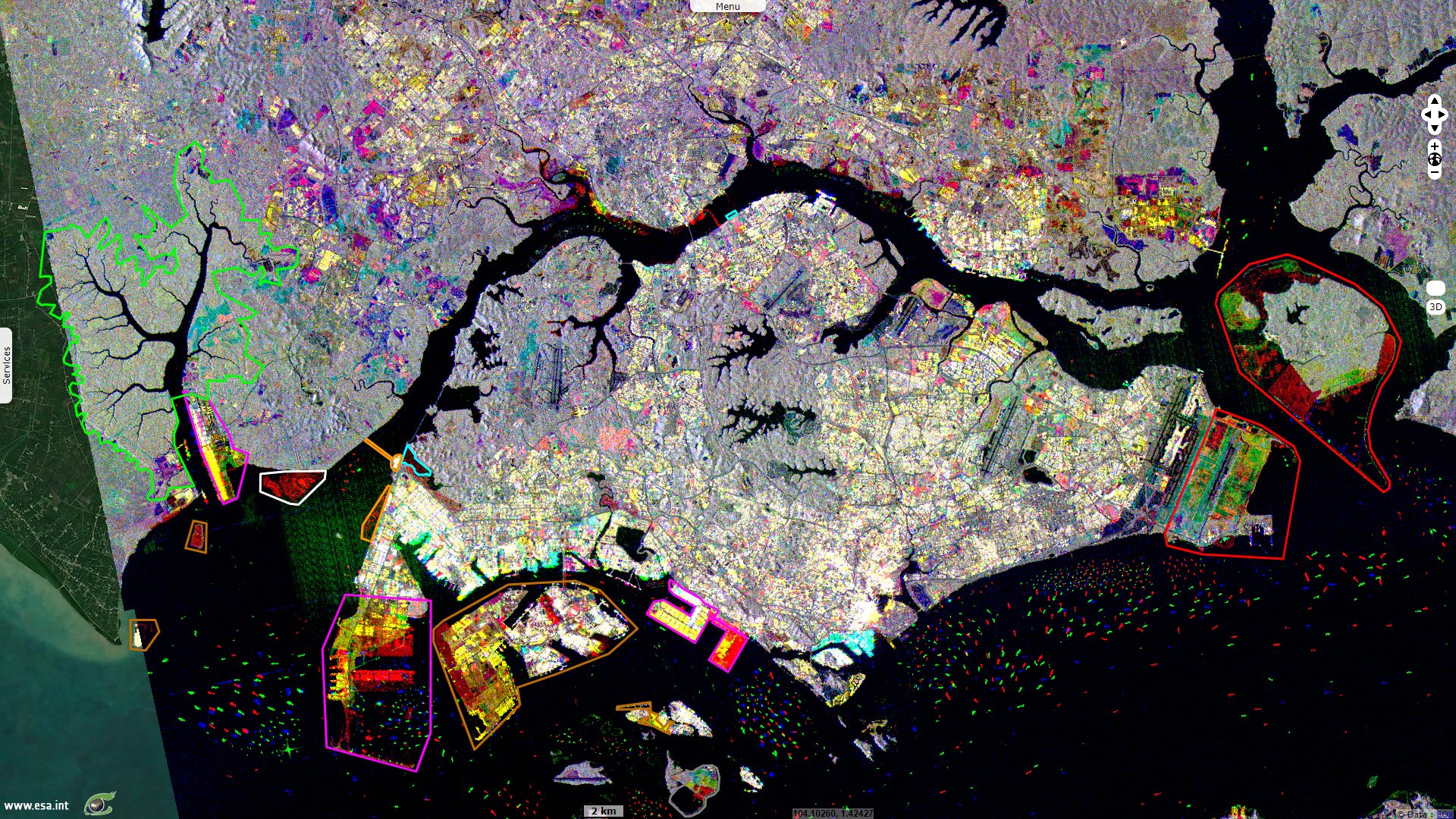

On the other side of the Straits of Johor, similar developments are taking place nearby protected areas. Oil and gas terminals rose from the sea at west, a major container port was built and a high standing city is being built on reclaim land. "The development is in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, just north of Singapore. It was built by Country Garden, China's largest property developer. Forest City is huge: It spreads across 1740 hectares, or four times the size of city-state Monaco. Around 700,000 people were initially expected to live in the estate." according to an article written by Marielle Descalsota for the Insider: "Construction on the $100 billion project started in 2015 and is expected to be completed in 14 years. It has lauded itself a 'living paradise' and a 'green, futuristic city.' But some experts believe Forest City is a 'time bomb,' as its rapid construction has wreaked environmental havoc on Johor Bahru's coasts."

"Forest City is partially built on reclaimed land from the Straits of Johor. Around 163 million cubic meters of sand were dumped into the ocean to build the city." "Some experts say the rapid speed of construction coupled with the reclamation of land is a dangerous combination. 'In spite of the technological innovations used to reclaim and build, sand dumped on mud seabed needs more than the publicised time to settle,'Serina Rahman, a Malaysia-based scientist and researcher, wrote in her 2017 book Johor's Forest City Faces Critical Challenges." "Cracks have appeared on some of the estate's buildings and sections of road have sunk into the ground., she added." reports Marielle Descalsota.

Regarding the impact on environnement: The pattern of land reclamation in the Straits of Johor — only part of which can be attributed to Forest City — has also led to a severe decline in the amount of fish local fisherman are able to catch, Serina Rahman said. 'Fishermen can hardly get 20 kilograms when they're out at sea,'. 'The boats are small and because of the land reclamation projects, they have to go further into the sea, making their jobs even more dangerous.' Country Garden spent $25 million in compensation to some 250 fishermen for losses in their catches, according to a 2018 report from environmental site Mongabay." but it seems all fishermen were not compensated and this money does not explain how to save this Ramsar wetland from further damage.

The Insider article states: But as of 2019, only around 500 people lived in the estate, according to a 2019 report by Foreign Policy. An expert who declined to be named for security reasons told me the estate's population has since grown to several thousand — which is still less than 5% of the expected number of residents. Prices in the development have soared in the past couple of years, the residential units were priced according to the then-booming housing market in China. Muhammad Najib Razali, a professor of real estate at Malaysia Technology University, has conducted extensive research on urban planning and real estate in Johor Bahru. 'The main reason is that the apartments are expensive — they are unaffordable for locals,' at around $2,900 per square metre. In 2017, the starting price for a smallish, two-room apartment was set at around US$170,000, later, condo apartments in the development retailed for as much as $1.14 million. For comparison, the average sale price of property in Johor Bahru, where Forest City is located, is $141,000. The median annual salary in Malaysia was around $5,651 in 2020.

Indicative of its clientele, the road signage was often exclusively written in Chinese while the few schools that opened only taught Mandarin. Following the 2018 change in Malaysian government and subsequent political uncertainty, the worsening geopolitical environment between Malaysia and China, and suspension of the Malaysia My Second Home long term visa scheme, some Chinese nationals (who formed the majority of buyers) decided to leave the development and sold their units at steep losses, further adding to the supply overhang.

Given the current lack of residents and the risk of default of the project's promoter Country Garden, it is very likely the project doesn't go to its planned end.