Bighorn Forest showcased for National Park Week

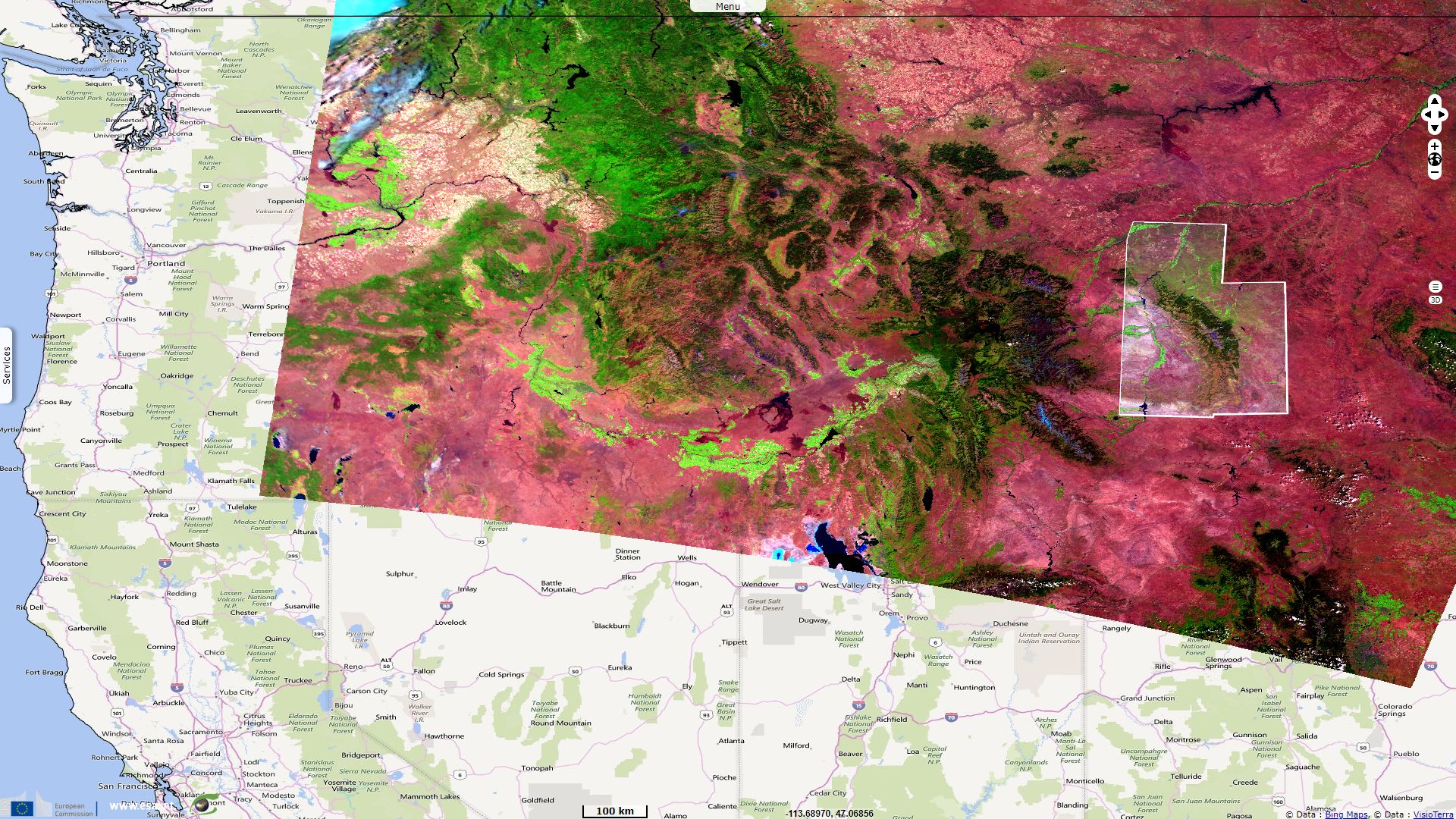

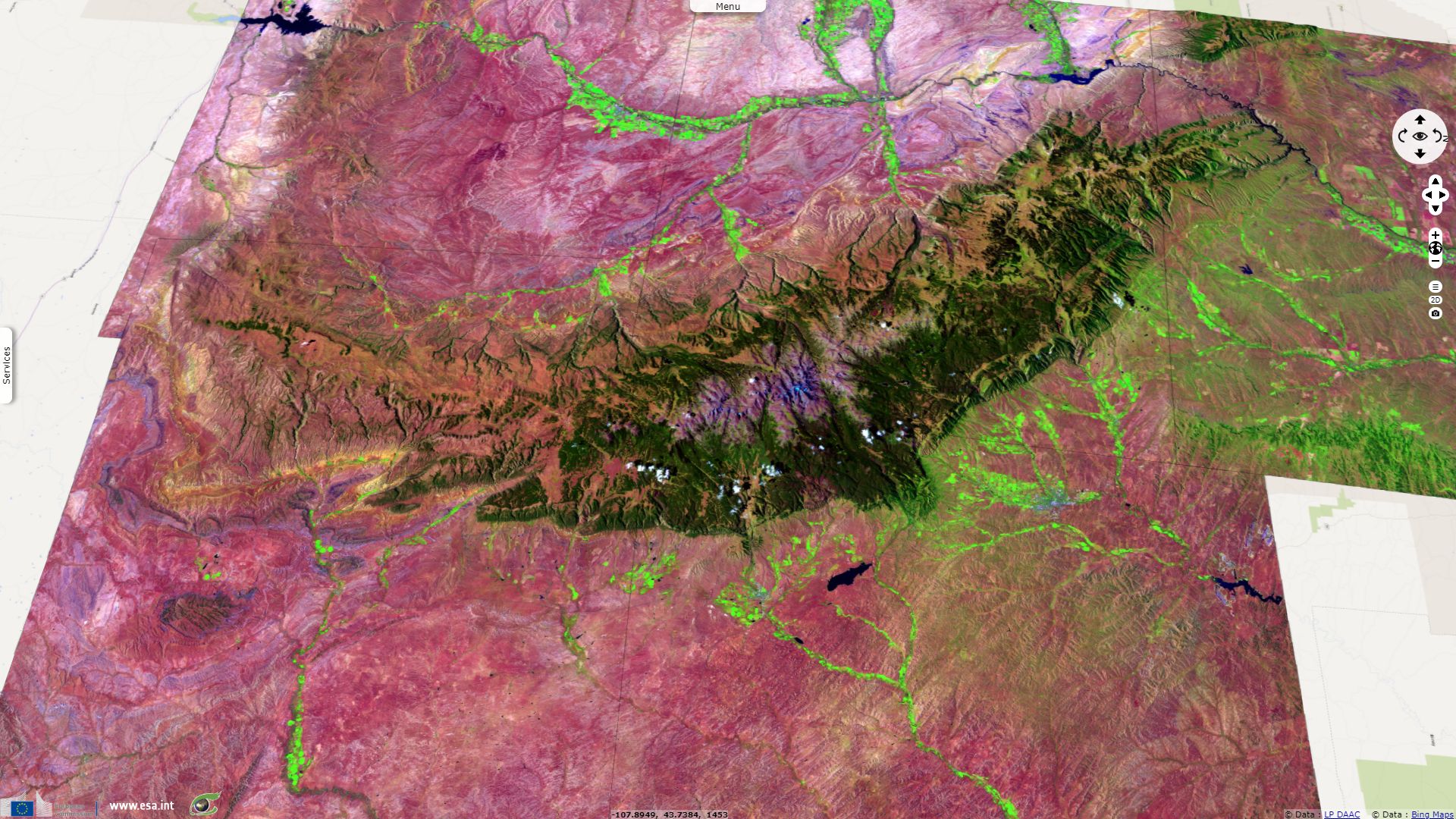

Sentinel-3 SLSTR RBT acquired on 18 August 2017 at 17:45:26 UTC

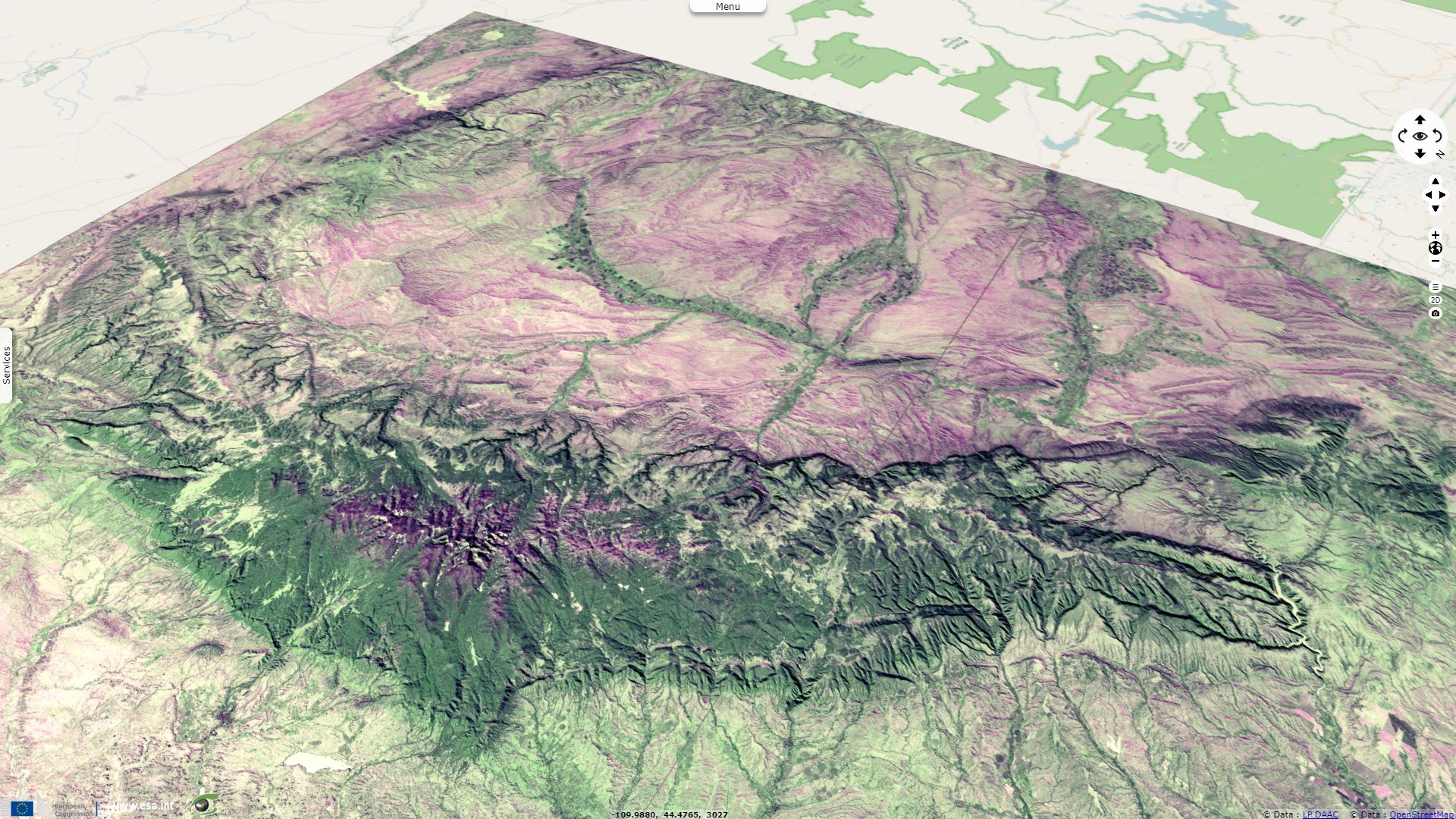

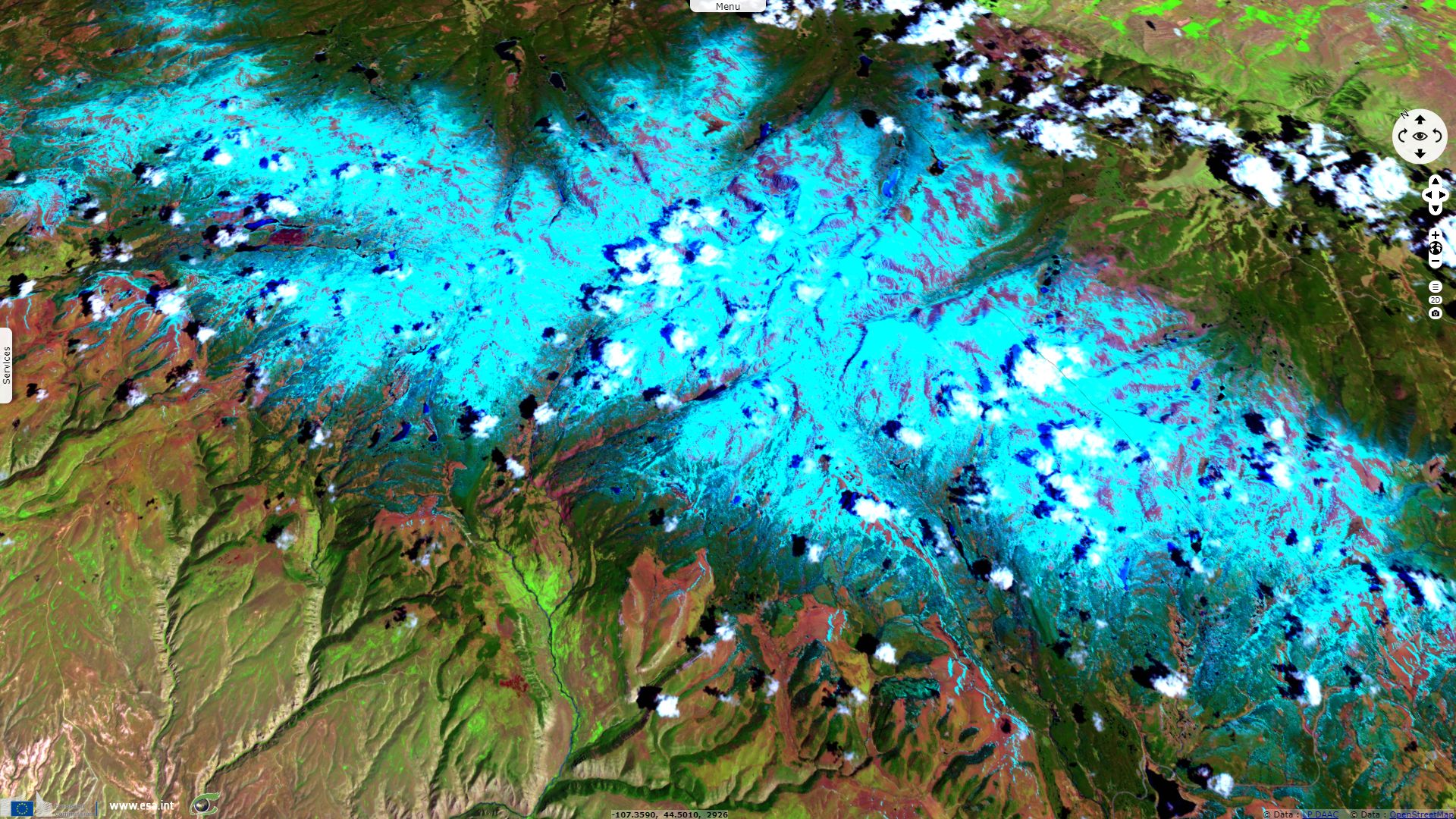

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 25 May 2018 at 17:59:09 UTC

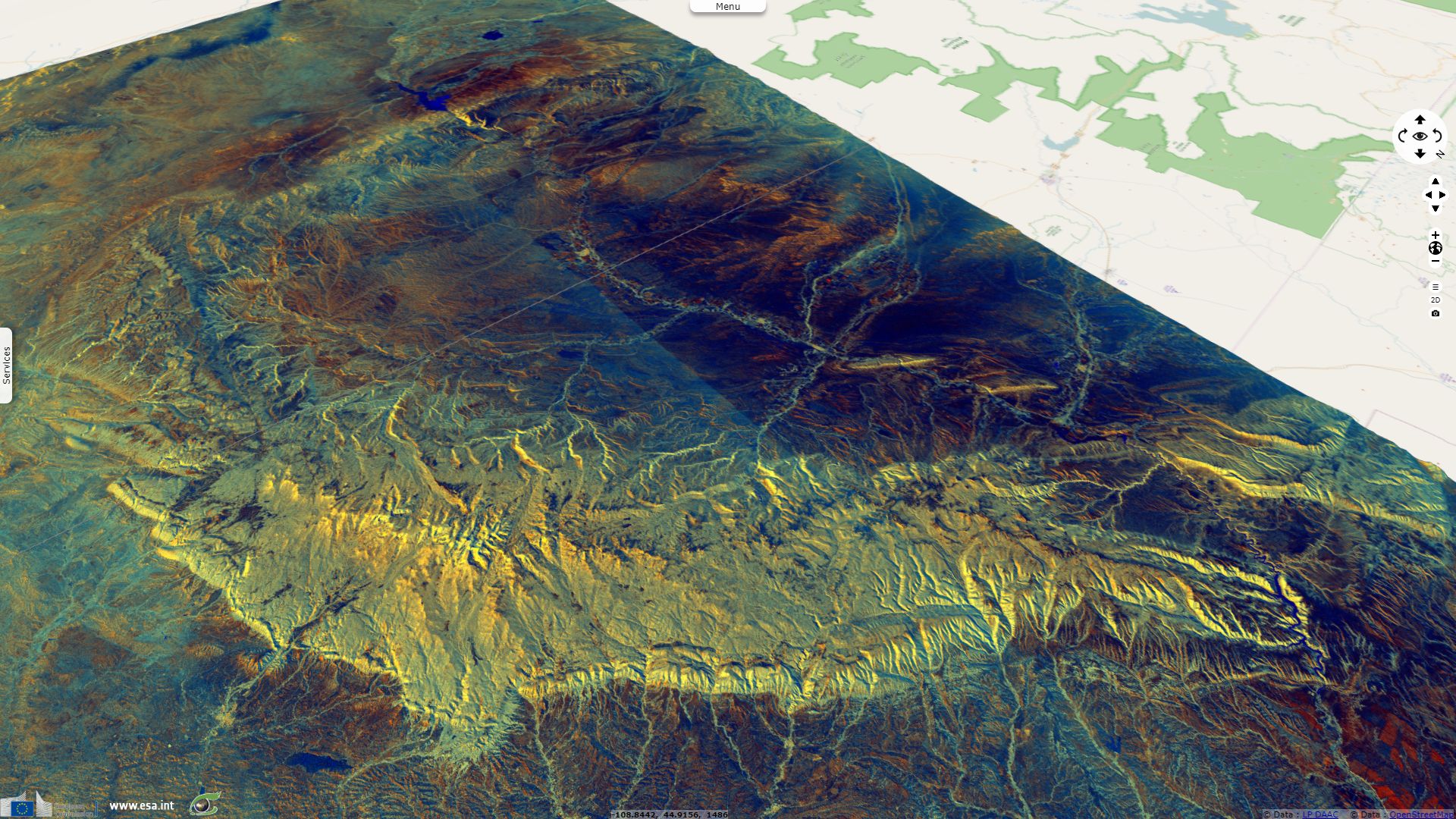

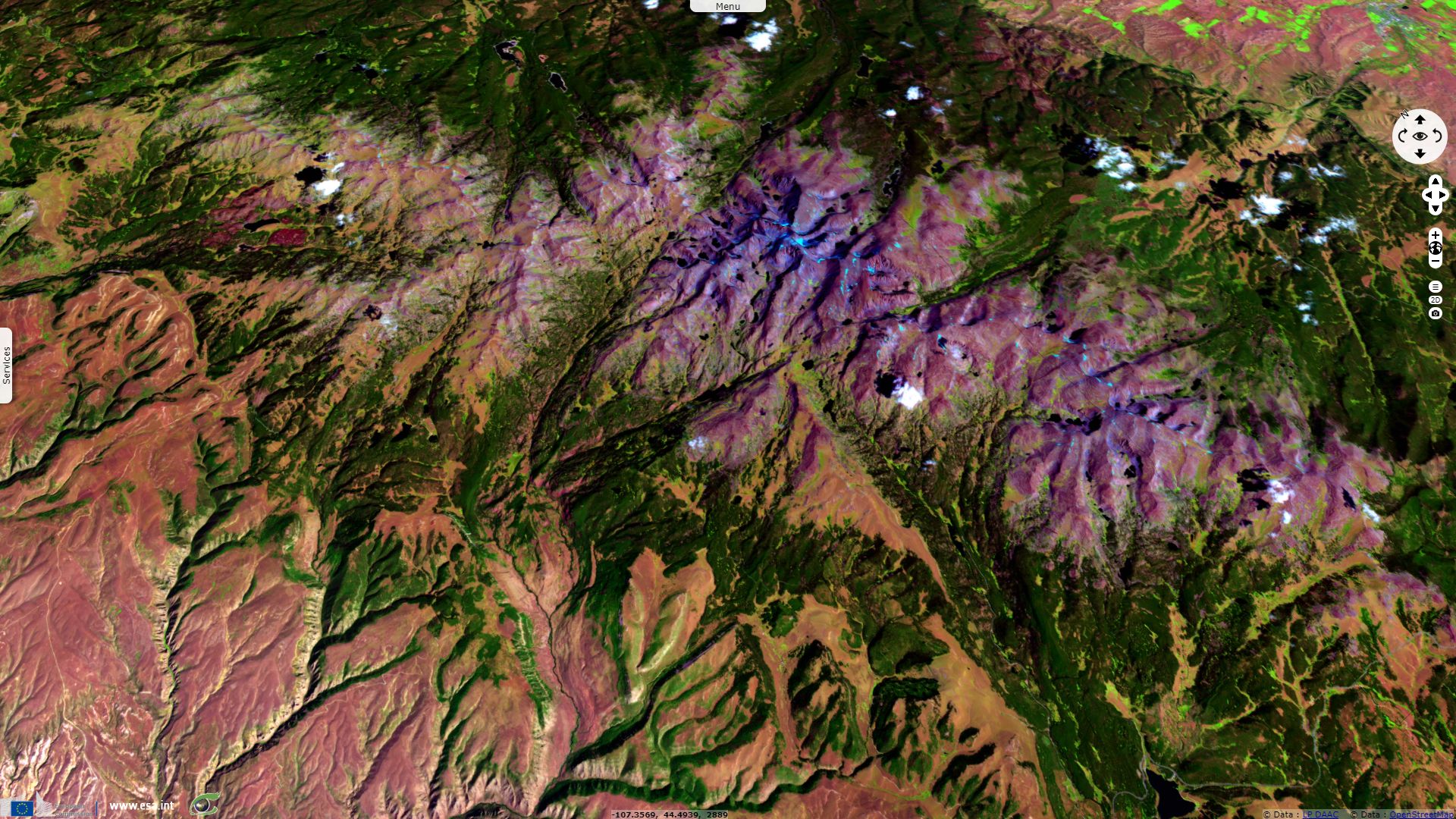

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 02 September 2018 at 17:58:59 UTC

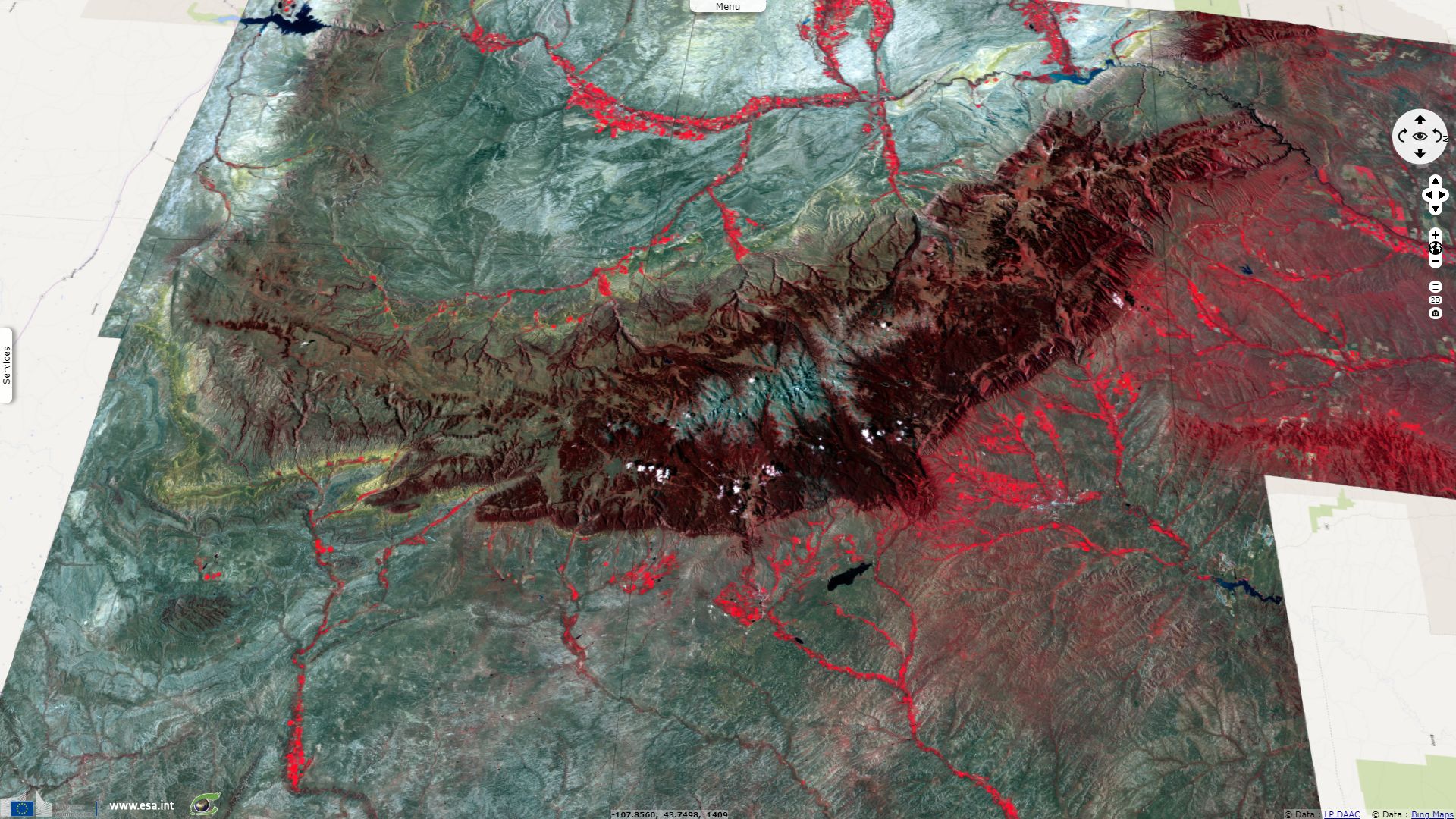

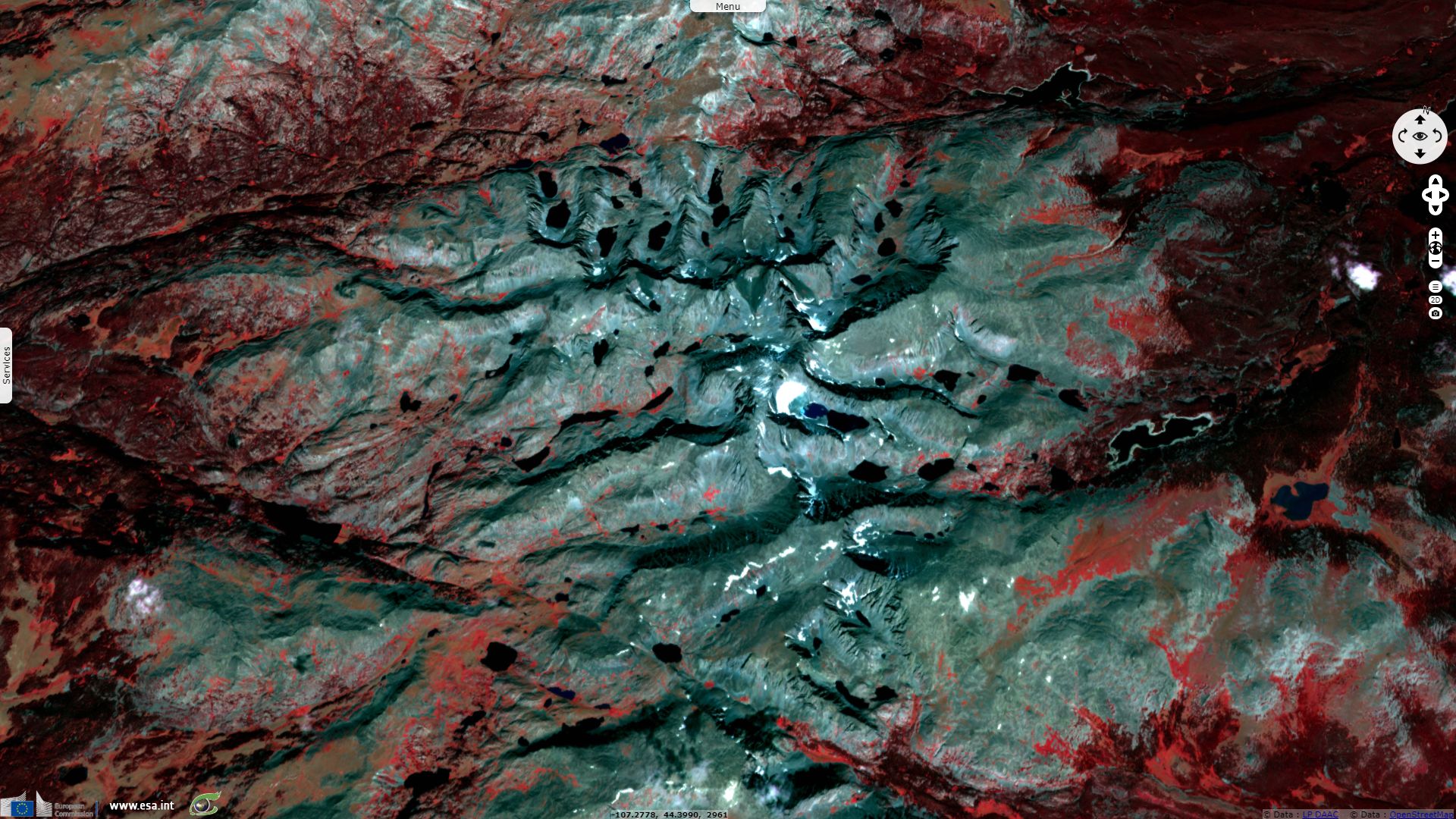

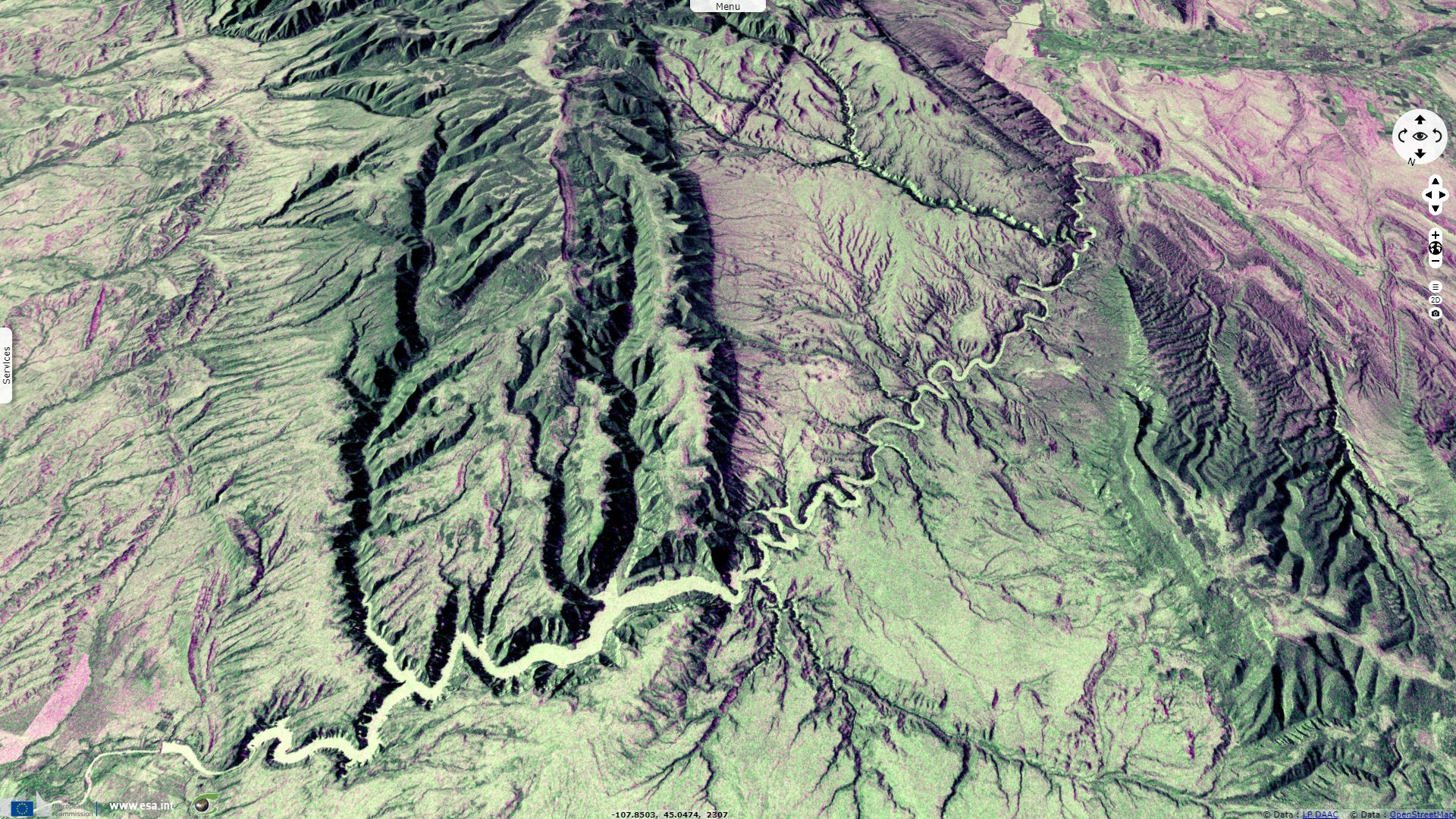

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 19 September 2018 from 01:02:49 to 01:03:14 UTC

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 03 April 2019 from 13:16:25 to 13:16:50 UTC

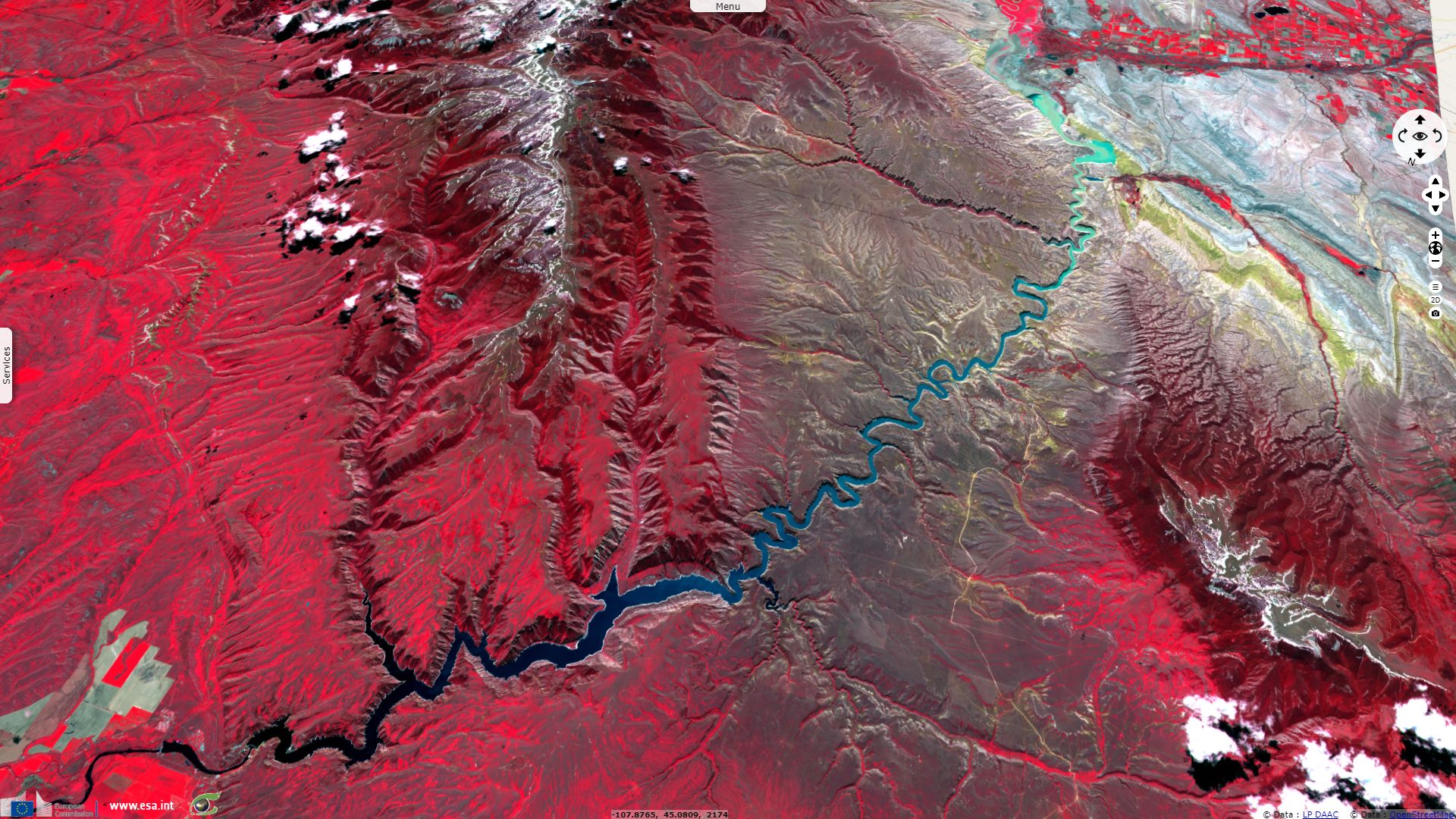

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 25 May 2018 at 17:59:09 UTC

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 02 September 2018 at 17:58:59 UTC

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 19 September 2018 from 01:02:49 to 01:03:14 UTC

Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 03 April 2019 from 13:16:25 to 13:16:50 UTC

Keyword(s): Land, mountain range, badland, canyon, river, lake, dam, glacier, snowmelt, erosion, USA, United States

The US Forest Service describes Bighorn National Forest writing:

"Located in north-central Wyoming, the Bighorn Mountains are a sister range of the Rocky Mountains. Conveniently located halfway between Mt. Rushmore and Yellowstone National Park, the Bighorns are a great vacation destination in themselves. No region in Wyoming is provided with a more diverse landscape - from grasslands to alpine meadows, clear lakes to glacially-carved valleys and rolling hills to sheer mountain cliffs."

Left: The gentle slope allows hiking to the top - Source: Andrea Davidson.

Right: Transition from montane forest to the subalpine zone to alpine tundra - Source: Todd Blythe.

It wrote about the central Cloud Peak Wilderness: "In 1984, Congress passed the Wyoming Wilderness Act, which designated the Cloud Peak Wilderness in the Bighorn National Forest. Long recognized as having some of the most majestic alpine scenery in America. For 27 miles along the spine of the Bighorn Mountain Range, the 189,039 acre Cloud Peak Wilderness preserves many sharp summits and towering sheer rock faces standing above glacier-carved, U-shaped valleys."

Wilderness Areas dedicated website adds: "Named for the tallest mountain in the Bighorn National Forest--Cloud Peak at 4015 m, the Wilderness is blanketed in snow for a large part of the year. Most of the higher ground is covered by snow until July. On the east side of Cloud Peak itself, a deeply inset cirque holds the last remaining glacier in this range. Several hundred beautiful lakes cover the landscape and drain into miles of streams. The forest is a mix of pine and spruce opened by meadows and wetlands. The high mountain lakes are the most sensitive to acid rain deposition in the Rocky Mountain Region as monitored and analyzed by lake sampling. Although rugged in appearance, the Bighorns are actually more gentle than other mountains in Wyoming."

Left: Fall Colors at Bighorn National Forest near Burgess Junction - Source: USFS Rocky Mountains.

Right: Looking up west tensleep creek - Source: Todd Blythe.

Centered within the Cloud Peak Wilderness of Bighorn National Forest, Cloud Peak Glacier is the only active glacier in the Bighorn Mountains. The glacier is in a deep cirque immediately northeast of Cloud Peak, the highest peak in the Bighorn Mountains. Cloud Peak Glacier lies at approximately 3600 m above sea level. Cloud Peak Glacier is retreating rapidly and is expected to disappear entirely sometime between the years 2020 and 2034. Between 1905 and 2005, the glacier has been reduced in size from an estimated 14 300 000 m³ to 2 200 000 m³.

The Bighorn range feeds the Bighorn river which has carved a deep canyon through the thick plateau that constitutes its basin. Geologist Paul Gordon introduces the canyon for the National Park Service: "About sixty-million years ago, a river meandered north to the Arctic Ocean across a continent vastly different from the North America of today. The land was already old, so old it is hard to grasp its antiquity. Even then, where the north bound river ran, change after change had taken place. Great oceans had come and gone; mountain ranges had appeared and eroded away. Beneath the place where the river flowed, bygone seas had deposited layer upon layer of sedimentary rock, including the massive formation today called the Madison Limestone through which modern Bighorn River has cut its way. There had also been climatic changes: long periods of warm or cool weather, times when rains poured upon the land, times when desert-like conditions prevailed."

Left: The trail winds into a large meadow that has been flooded by spring runoff - Source: Todd Blythe.

Right: A large meadow north of mistymoon lake - Source: Todd Blythe.

"Life had changed as well as the land and the climate. The early seas that covered this land had been home to myriads of creatures whose fossils are entombed today in Bighorn Canyon’s limestone. Land creatures had also walked this country; the long age of the dinosaur had already come and gone. These great creatures had roamed this land and disappeared, leaving only enough evidence of their existence to tantalize and intrigue us. Mammals had inherited the plains and the banks of the river. Camel, horse, mammoth, musk-ox, and lion were among their number. Like the dinosaur, they in turn would vanish. Plants had also changed. Simple onecelled species, fl owering shrubs, grasses, and fi nally massive trees had appeared, lived their span, and disappeared."

"But still change was ongoing, as deep beneath this scene, the earth stirred and rumbled. The land rose, at times rapidly and at other times only infinitesimal fractions of an inch in decades. The river clawed at its bed, at times keeping pace with the rising of the land, at times blocked in its rush to the sea forming natural lakes. In time natural dams were eroded, allowing the river to travel on, in its never ending alteration of the land."

Left: A view of glacier lake and the glacier on the backside of cloud peak - Source: Todd Blythe.

Right: Looking south at bomber mountains from the summit of cloud peak - Source: Todd Blythe.

"But still change was ongoing, as deep beneath this scene, the earth stirred and rumbled. The land rose, at times rapidly and at other times only infinitesimal fractions of an inch in decades. The river clawed at its bed, at times keeping pace with the rising of the land, at times blocked in its rush to the sea forming natural lakes. In time natural dams were eroded, allowing the river to travel on, in its never ending alteration of the land."

"This process has continued throughout the ages. In time the Bighorn and Pryor mountains came to dominate the landscape, at times rising slowly, and at other times pushing upward through seismic activity. As the water whittled away at the landscape, carving Bighorn Canyon and its tributaries, the Bighorn was loaded with vast amounts of sediment. This served as an abrasive, wearing away the rock beds of the river and drainages, gouging loose more material to be carried downstream, some as far as the Gulf of Mexico."

Aerial View of Yellowtail Dam from the east - Source: National Park Service.

"The construction of Yellowtail Dam in the 1960s had the most dramatic infl uence of any event ever on the canyon-cutting actions of the Bighorn River. The dam changed the rapidly fl owing, silt-laden stream into a gentle moving lake. When the river lost it velocity, it also lost its ability to maintain its load of eroded material. Mud and silt quickly settled to the lake bottom, creating deposits over thirty feet thick in the southern portions of the lake."

"Prior to the construction of Yellowtail Dam, the Bighorn was not only muddy and silt-laden, but its water volume also fl uctuated. The dam regulates downstream flows and the river runs clear, its load of sediments left behind in Bighorn Lake."

"Yellowtail Dam, like all man-made objects, is temporary, when measured in geological time. Canyon cutting and mountain building are measured in millions of years. The life of a dam is measurd in hundreds. So even now, the water’s work continues."

Left: Geologic upheavel beside Bighorn Lake - Source: National Park Service.

Right: Aerial view of Bighorn Canyon Near Devil Canyon - Source: National Park Service.