Luanda, an agglomeration indirectly shaped by civil war & resources extraction

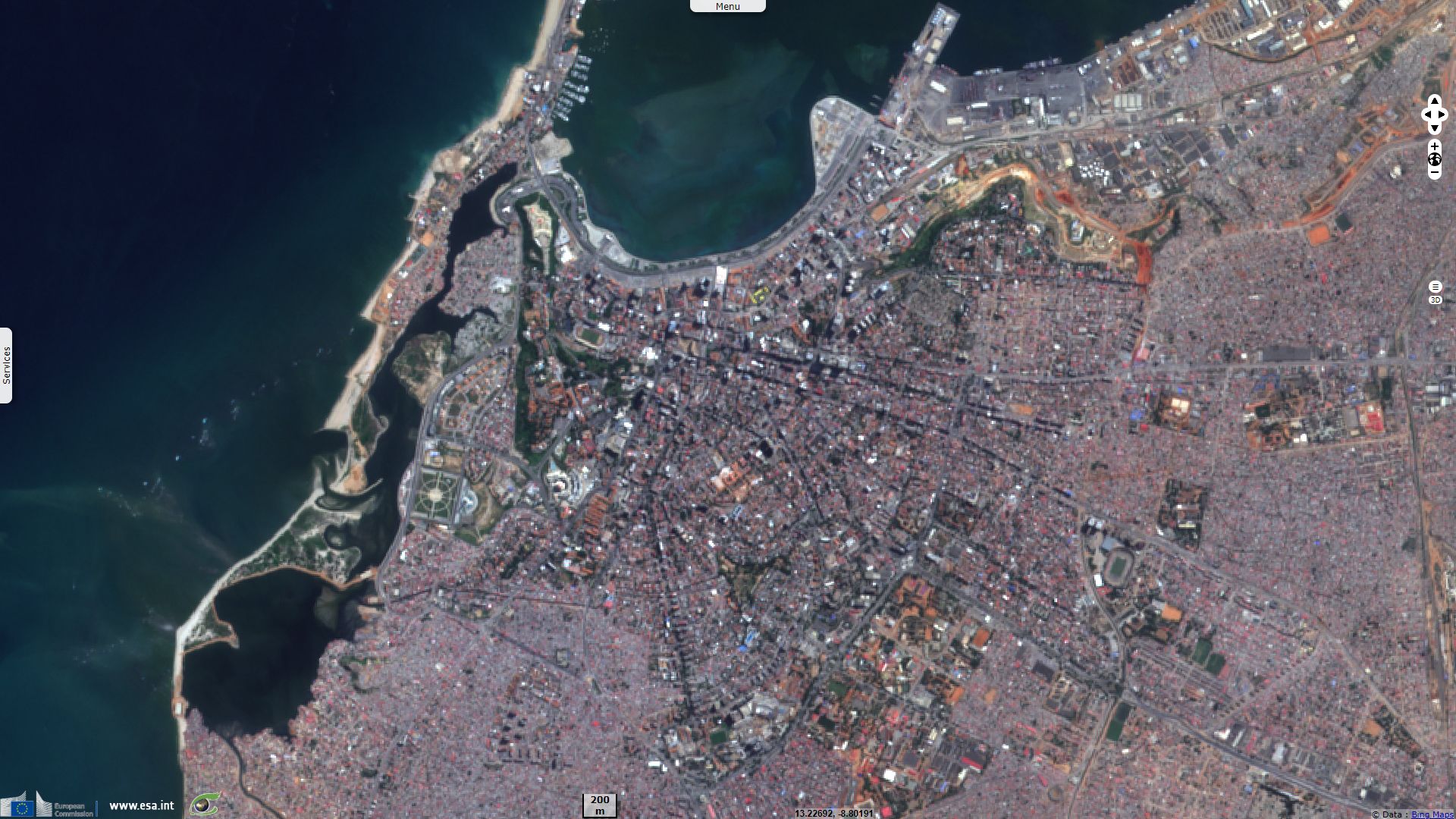

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 21 May 2016 at 09:06:02 UTC

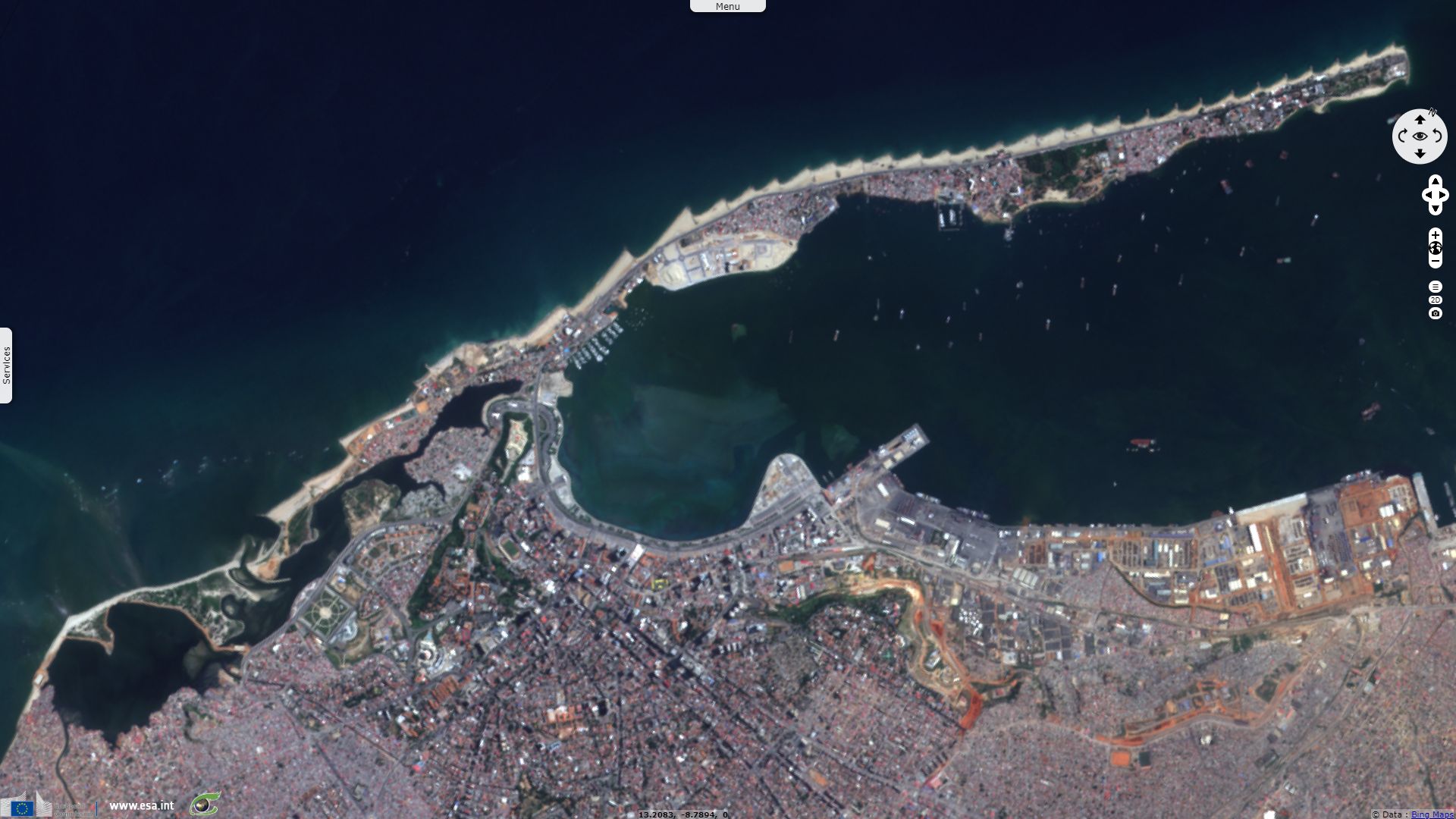

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 07 November 2019 at 09:10:59 UTC

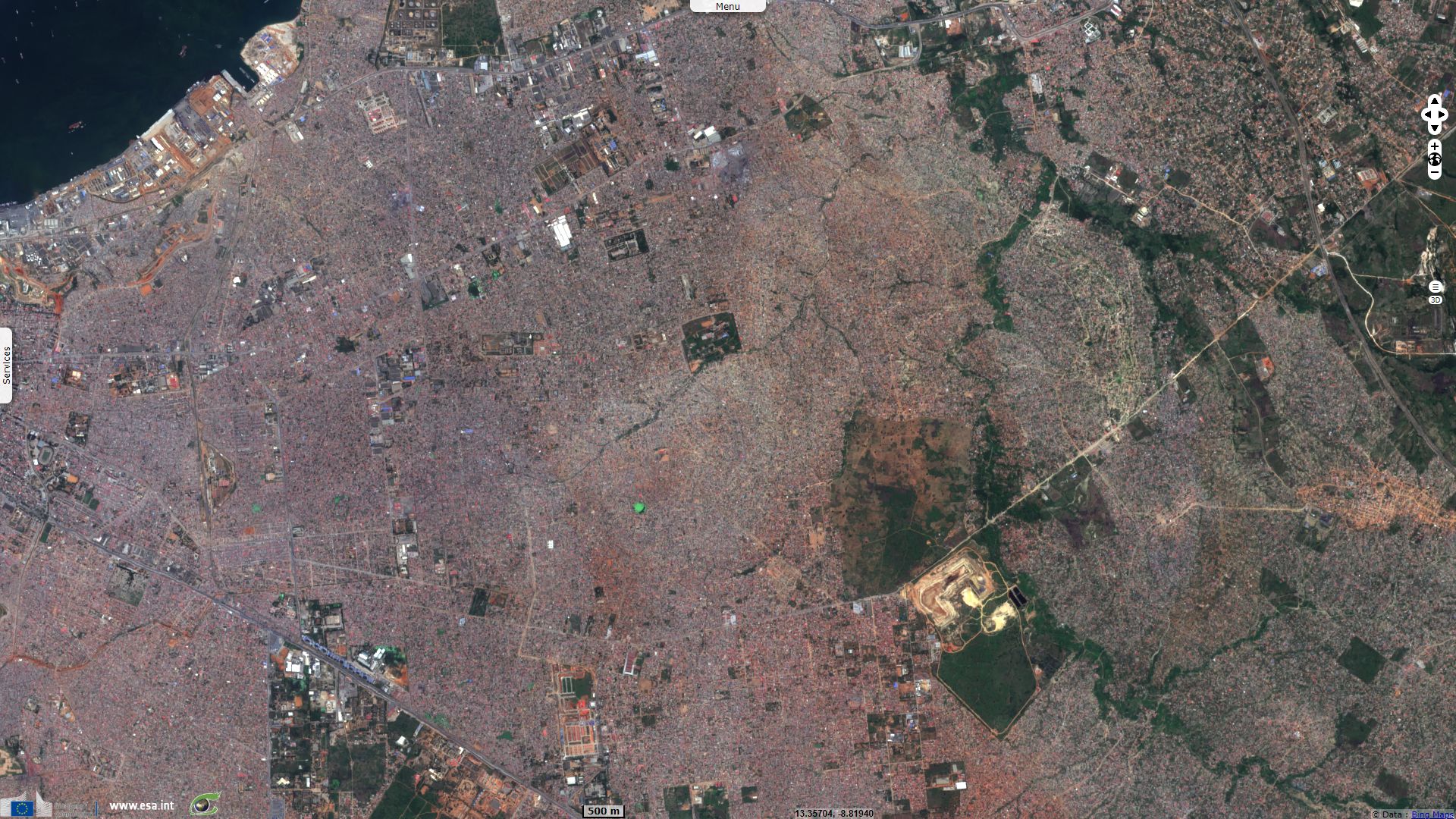

Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 07 November 2019 at 09:10:59 UTC

Keyword(s): Urban growth, infrastructure, natural resources

The Angolan war of independence lasted from 1961 to the Portuguese Carnation revolution in 1974. "For the next twenty-five years, Angola fell into one of the most destructive civil wars in modern history. At least a million people died. By most estimates, roughly ten million land mines were buried—many of them remain active—scarring a territory twice the size of Texas and making large-scale agricultural planning nearly impossible. The war was fought as much for oil and diamonds as for ideological reasons, but it also served as the last major proxy battle of the Cold War." wrote Michael Specter for the NewYorker in 2015.

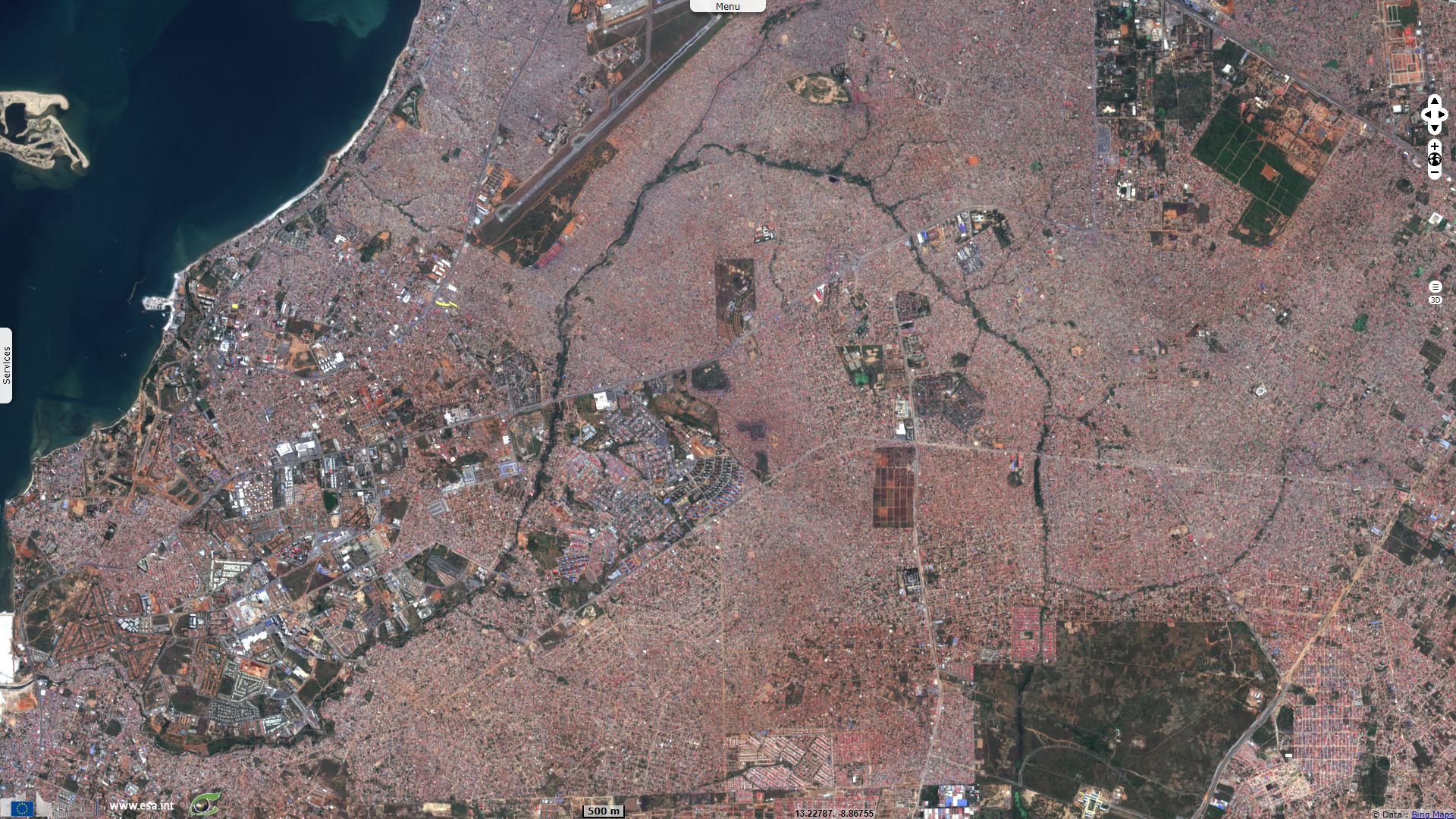

The population of Luanda has grown dramatically due in large part to war-time migration to the city, which was safe compared to the rest of the country. At the end of the civil war, Luanda lost several hundreds of thousands of inhabitants but its population quickly soared again. The population of Greater Luanda has roughly doubled every nine years since the 30s, from 18 000 in 1934 to 8 000 000 in 2019. Around one-third of Angolans live in Luanda, 53% of whom live in poverty.

"The Marxists — the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) — with support from the Russians and led by Agostinho Neto, who later became the country’s first President, relied on an unusual mixture of Eastern European economic advisers and Cuban soldiers. Neto condemned the influence and the power of Western oil companies, but understood that his regime and the country probably wouldn’t survive without them." continued Specter.

Oil production began in the Cuanza basin in 1955, in the Congo basin in the 1960s, and in the exclave of Cabinda in 1968. High international oil prices and rising oil production have contributed to the very strong economic growth since 1998, but corruption and public-sector mismanagement remain, particularly in the oil sector, which accounts for over 50 percent of GDP, over 90 percent of export revenue, and over 80 percent of government revenue (99.5% of Angola's exports came from just oil and diamonds in 2006).

As a result, "The average national salary in 2010, the latest year for which official data is available, was around $260 per month. In the finance sector the average was 10 times higher and in the oil business over 20 times higher, or around $5,400.", reported Shrikesh Laxmidas for the Independant in 2014.

Resource extraction is vastly more lucrative and out-competes other industries. This large gap is responsible of a resource curse phenomenon in Angola. One of its symptom is its "Dutch disease": as revenues increase in the growing sector (or inflows of foreign aid), the given nation's currency becomes stronger (appreciates) compared to currencies of other nations, manifesting in its exchange rate. This results in the nation's other exports becoming more expensive for other countries to buy, and imports becoming cheaper, making those sectors less competitive.

Depending on the country's gouvernance, the abundant revenue from natural resource extraction may discourage the long-term investment in infrastructure that would support a more diverse but then less performing economy. While resource sectors tend to produce large financial revenues, they often add few jobs to the economy, and tend to operate as enclaves with few forward and backward connections to the rest of the economy.

According to the rentier state theory, Angola is highly vulnerable to the volatility of the price of its key resources. It makes the balance of the budget of the country susceptible to large unpredictable variations. when the price of the resources fall, the deficit soars, the government debt rises while its GDP shrinks, causing the interest rates and thus the debt burden to rise, even moreso if it has to be repaid in foreign currency. In 2015, Michael Specter exemplified this: "The current price of a barrel of oil is about fifty dollars, but just a few months ago the Angolan government, for the purposes of its 2015 budget, assumed that the average price would be eighty-one dollars. That gap will prove hard to close. The Dos Santos government announced earlier this year that it would cut the budget by a quarter, and it has said that it will work harder to diversify the economy. Few economists who study Africa believe that it will be easy."

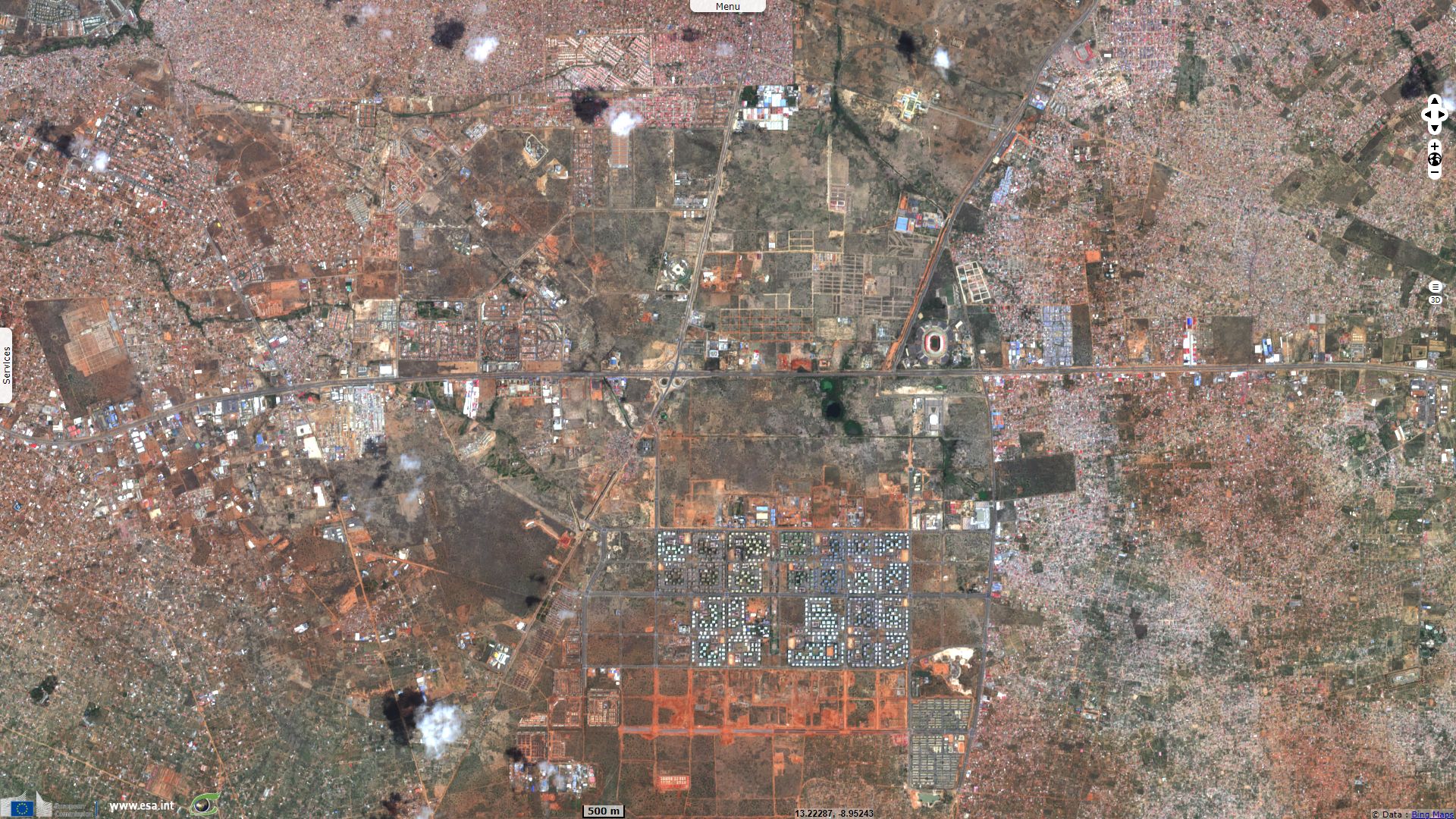

During the civil war, Luanda became a site of refuge for those affected by the conflict, leading to a rapid expansion of the musseques, literally “places of red earth” in kimbundu language, around the city centre. Equivalent to Brasilian favelas, these constructions spread anarchically between narrow irregular dirt roads. Often made of assembled materials, they lack foundation, sanitation, running & drinking water and electricity.

Michael Specter described the situation: "Per-capita income in Angola has nearly tripled in the past dozen years, and the country’s assets grew from three billion dollars to sixty-two billion dollars. Nonetheless, by nearly every accepted measure, Angola remains one of the world’s least-developed nations. Half of Angolans live on less than two dollars a day, infant mortality rates are among the highest in the world, and the average life expectancy — fifty-two — is among the lowest. Obtaining water is a burden even for the rich, and only forty per cent of the population has regular access to electricity. (For those who do, a generator is essential, as power fails constantly.) Nearly half the population is undernourished, rural sanitation facilities are rare, malaria accounts for more than a quarter of all childhood deaths, and easily preventable diarrheal diseases such as rotavirus are common."

In an article published on 22.01.2019 in the Guardian, Sean Smith wrote: "In recent years it has competed with Hong Kong and Tokyo for the title of world’s most expensive city for expatriates. Cranes dominated the downtown skyline and homes in the surrounding areas were demolished to make way for Chinese-backed housing projects."

"New import tariffs imposed in March 2014 made Luanda even more expensive. The stated aim was to try to diversify the heavily oil-dependent economy and nurture farming and industry, sectors which have remained weak." "Oil output has soared since 2002, but the south-west African nation’s agriculture and industry are relatively undeveloped. They make up 17 percent of gross domestic product, compared with oil’s 41 percent.", Laxmidas added in 2014.

Michael Specter added "Economist Valimamade says many challenges remain for Angola to deliver on its farming and industrial potential. 'The business environment has to improve... It is being done but the government itself says efficiency on big projects isn’t satisfactory.' Critics say a small group of business owners with ties to the government may benefit most from the tariff hikes"

"Downtown Luanda, where wealth and extreme poverty exist side-by-side." - Source: Sean Smith for the Guardian

"Right: A melon can cost a hundred dollars; most Angolans make less than two dollars a day."

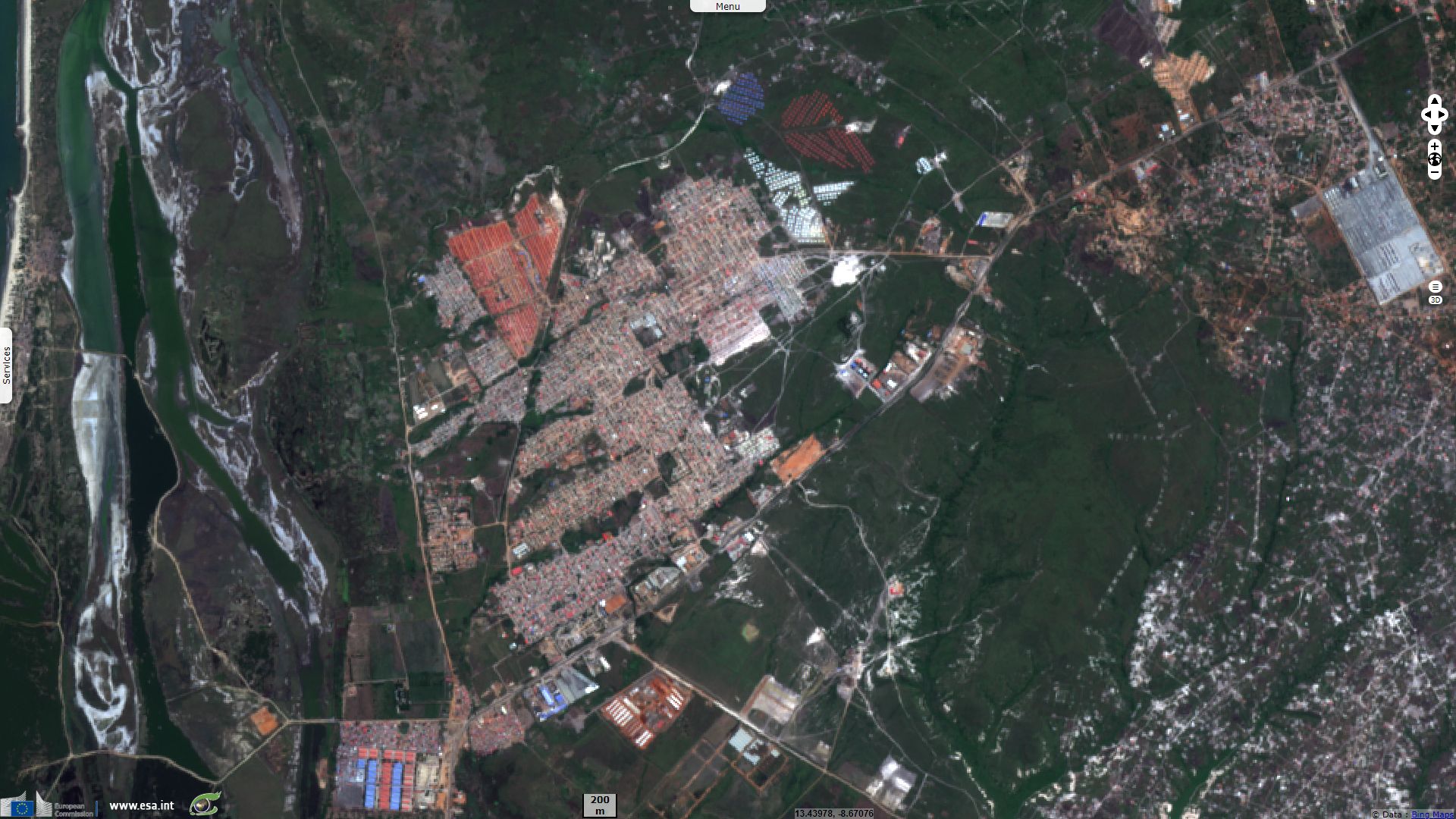

Dr Chloé Buire of Africa Research Institute wrote in 2015: "Contemporary Luanda exhibits a remarkable tension between unplanned sprawl, resulting from self-construction from below, and attempts to regulate from above, through eviction and demolition. In the absence of urban planning, population densities in the musseques exceed 100 000 people per square kilometre, while there is a shortage of land on which to build new roads, bridges and drainage canals. In their quest to construct a modern city, the MPLA resolved to demolish informal settlements which occupied precarious positions on hillsides or on riverbanks prone to flooding and landslides, and resettle their residents in new Social Housing Zones."

Cost and living and price of housing have exploded since 2002, to a point it is comparable to the costliest cities in the World. Unable to rent an appartment in these new, equipped but far-away settlements, a large part of the workers, even those with stable jobs have been pushed away from urbanized quarters of Luanda.

Sean Smith explained: "A new housing development in Kilamba, to the south of the city, is one of many neighbourhoods constructed by Chinese developers. Existing homes were razed, with former residents offered spaces in the new buildings. In one development we visited, the rent was four times the average monthly wage." Responsible for their sale was Delta Imobiliária, a corporation linked to influential figures in the MPLA, state oil company Sonangol, and the military. "For a while developments like these lay empty, dubbed ghost towns."

Dr Chloé Buire adds: "In February 2013, President dos Santos ordered that the apartments be made affordable and the state-backed mortgage scheme open to all Angolans. When the smallest unit (T3) dropped in price from US$125,000 to US$70,000, Kilamba suddenly became Luanda’s most accessible property market."

"Plots were reserved for hospitals and schools, the ground floor of some residential blocs were allocated for commercial use, and green spaces and sports pitches built." They are still to be built to this day.

The main airport of Luanda is Quatro de Fevereiro Airport, which is the largest in the country. Currently, a new international airport, Angola International Airport is under construction southeast of the city, a few kilometres from Viana, which was expected to be opened in 2011. However, as the Angolan government did not continue to make the payments due to the Chinese enterprise in charge of the construction, the firm suspended its work in 2010. It is not unusual according to an Angolan source, public money has to go though several intermediates to reach its recipient, at the end a lot has disappeared and projects are not completed.

Things might change, Sean Smith reported: "In last year’s election, José Eduardo dos Santos, the president that succeded Neto for almost four decades, was replaced by João Lourenço, a former defence minister. There appears to be some appetite for reform in parts of the new government: most notably, several lucrative contracts given to Isabel dos Santos, the former president’s daughter and Africa’s richest woman, were annulled by the new president."